Salman Rashid started this story at

Musa’s rock with the hole and the roof Through the night the gusting wind kept at it. At sometime after five the sun broke through the shackling layers of gray haze and appeared as a pale yellow disc levitating just above the horizon. It was time to take the short walk to the crest of the ridge of Bail Pathar.

I am no mountaineer and though I’ve been in some high places, I have never actually climbed a real peak. But one thing I know: even insignificant peaks, simply by their very nature of being peaks and therefore higher than the surrounding ground, offer something more than just great views. It was here where long before the dawn of history primitive man placed his gods. Peaks were sacred. Whether it be the puny Miranjani near Nathiagali; or the 4800 metre Deo nau Thuk (Peak of the Jinn) on Deosai; or Musa ka Musallah in Kaghan; or Ilam in Swat; or Kutte ji Qabar (The Dog’s Grave) in the Khirthar Mountains; or Takht e Suleman, they, one and all, were revered places. Those were places for man to approach in worshipful and reverent state of mind, perhaps with an offering or two for whatever gods man believed in.

These gods were created not as man regarded the peak from the base. They were created only after our ancestors were driven up by that curiosity that made them human as distinct from the other primates. Upon the mountain, at the apex of human endurance, the excitement of the panorama those primitive eyes beheld was paled by the heightened consciousness of man’s own place in the great scheme of things. This realisation then as now is not of grandeur and supremacy, but of inconsequence and paltriness – man’s real station in the grand scheme of things. This is the light that removes the last swagger from lowly humans. On some hilltops (Tilla Jogian near Jhelum, for example) this awareness is higher than on others. And so it was that high places the world over became the seats of gods.

If this is the marvel insignificant peaks such as I have named can work, surely the highest places on earth would do the same many times over. Alpine and mountaineering clubs should therefore bear the motto, ‘Discover thyself.’ And if you ask me, that is the reason women and men have climbed whatever mountain is available – not ‘because it is there.’

Immediately below us to the east right where our camp was spread out was Sahib Talab – the Sahib’s Pond, glinting in the dull light of the hazy morning. Far beyond that was a blue-gray ridge and then the plains. On clear nights the lights of Dera Ghazi Khan and Taunsa, and on clear days the silver ribbon of the Sidhu River could be seen, we were told. To the west a wide valley, scoured by four dry streams, spread at the foot of our mountain. Beyond, rose a khaki ridge and on its other side Balochistan was spread out all but unseen in the dust haze. To the north were more hills and to the south a round knoll, the highest part of the Bail Pathar ridge, blocked further view.

Risaldar Yaqoob Shah of the huge pot-belly, the trencherman of this journey, had earlier told us the story of the bull and the boulder: once upon a time a Baloch came up this mountain with his bull. Tying the animal to a boulder, he went about some business and when he returned he found the animal dead. Since that day the boulder was considered possessed and if anyone tied their animals to it the animals died. End of story.

As stories go this one was the most banal and unimaginative, even rather stupid. Neither is a boulder called pathar in Balochi, nor a bull a bal. Furthermore the first part of the name is clearly pronounced ‘Bail’ and not ‘Bal,’ consequently the story could not be true. The origin of the name is lost in the mist of time and in the tradition of all self-styled thinkers who invent heroes (sometimes events) to match place names (Kamalia and Qabula are two pertinent examples in Punjab), some moron thought up this yarn. I hotly debated the point until Yaqoob Shah lamely said since ‘bail’ in Urdu was an ivy or creeper, it might be that there was a stone on this hill that was carved with such a form. The poor man got no respite and this notion was shot to pieces very quickly. How could it be, it was asked, that a whole mountain was named after some rock or the other and no one even knew where the rock was?

But back on the top of the ridge Rehmat Khan had arranged tea for us. We sat in the blustering wind and drank the sweet brew as he told us of the angrez woman. It was about thirty years ago that a white woman was found wandering about near a village at the eastern foot of the mountain. The man who first found her, being a true Baloch, asked her to wait in an otaq (guest room) and went off to fetch someone who could understand her language. When he returned the woman was gone. Disappeared. Therefore, it was swiftly deduced, she was a spy. Moreover, the woman had shown the man a map with the Bail Pathar school marked on it. The school with its roster of one teacher and ten pupils on a map! That was sufficient for anyone who doubted her being a spy to now be fully convinced.

The following day, the woman turned up in Rehmat Khan’s village on the west side of Bail Pathar. She must have been one hell of a walker to have gone up and down the desiccated hill without succumbing to dehydration. Word, travelling by the Baloch tradition of hal-ahwal, had already arrived and folks were about waiting for her. She was quickly bundled off to the authorities at Dera Ghazi Khan. Raheal suspected she might have been the good Dr Ruth Pfau, guardian angel for lepers in Pakistan, hunting for unreachable lepers, but Rehmat Khan put on a saturnine countenance, lips down-turned, and nodding gravely said, ‘ No question. She was a spy.’

One wonder, though, what some crazy white woman should be spying for in the parched wastes of west Punjab hill country. But more than that one wonders what the building that everybody thought was a school was actually being used for to have been so prominently marked on the spy’s map. Now that was something either straight out of an unlettered man’s mind or very, very mysterious indeed and worthy of the files of our intellgence agencies.

The story of Sahib Talab, on the other hand, was cannier. Howard, a Deputy Commissioner of the early 1940s, once visited this mountain. He found it dry and barren, perhaps because of a drought, and local shepherds greatly distressed. The good man ordered the pond to be excavated that has ever since been called the Sahib’s Pond. In the worst years of the drought that now seems to be coming to an end, the pond had run dry only a couple of times. But the nearly continual rains since December have filled it up besides generally greening the region.

We returned to camp in time for breakfast. Over the meal we discovered that Rehmat Khan was not permitting departure without lunch. That would mean travelling during the hottest part of the day and, worse, another roast lamb. But no amount of pleading worked. We resigned, asked him to have the blue and orange canopy put up again and sat back under its shade.

The Inspection Book was produced and Raheal showed me a past entry. Dated the last day of June 2001, it recorded Raheal’s first visit to Bail Pathar in the capacity of Political Agent. He is a strange person, this Raheal. I know for a fact that as Political Agent he was the first one since 1947 to visit some places in his jurisdiction in the tribal outback of Dera Ghazi Khan. Having travelled with him before I have seen Inspection Books inscribed by officers of the Raj in 1947 and then by Raheal. In the intervening half a century no Pakistani official had deemed it fit to visit those areas!

The point of interest in the notation from June 2001 was that having enjoyed his trip to Bail Pathar, Raheal had ended his note saying he would like to return to the mountain with me. His wish, he said, had come true. The visit back then was work for Raheal had cases to dispose of. This time around it was just something we had to do together. Meanwhile, word had got around that Raheal was visiting the mountain and soon a delegation of liberally turbaned Baloch elders arrived with their entourages. These latter were perambulatory arsenals and could have started a small war on Bail Pathar. Solemnly the elders sat cross-legged and presented their petitions to the sahib.

Having come with supplies Raheal, a trained medical doctor, had turned his earlier visit into a medical camp. Scores of women turned up to be treated for night-blindness He had distributed the necessary vitamins and we now learned that nearly all his patients were cured. As a result women unable to attend that first camp were asking for treatment and Raheal promised to return with medical supplies. Men travel to cities and get their requirement of a varied diet. But women, the lower order of humanity in a tribal setting, eating only the leavings of their men, unacquainted with fruit and vegetables in a harsh land that produces nothing but some cereal, are seriously malnourished. Raheal had only discovered the tip of the iceberg. The sloth-afflicted officials of the Department of Health unwilling to undertake such hard journey find it easier filling in registers in the comfort of their offices while the poor and the unknown of Jinnah’s Pakistan living on the edge of the Middle Ages continue to suffer in silence.

Midmorning was lunch time on Bail Pathar and I hoped I was seeing the last roast lamb for several years. Rehmat Khan said it was impolite to turn down a Baloch’s hospitality and that men so spurned are known to have forsworn their wives if the guest did not relent and accept the proffered hospitality. The word is zan talaq and it is used as a sort of a binding not only upon the one who utters it to do or not do something, but also upon the corrival to acquiesce. That was something like the boys’ rhyme of the Lahore of the 1950s that made all those ‘son of a pig’ if they didn’t take up whatever challenge was thrown. For my part, in order to forestall the hazard of more roast lamb I loudly declared, for all to hear, that I would stand divorced from my wife if Rehmat Khan and his people fed us one more time.

This took everyone by surprise. Such a thing was unheard of among the Baloch. One never said zan talaq in order to ward off hospitality. But I had said it and I was standing by it. Nevertheless as we walked down the mountain every time Rehmat Khan mentioned the possibility of more roast lamb at his brother’s home, I reminded him of my avowal. That led to the story of the large-hearted Baloch and his stingy wife who were visited by the man and his naseeb.

We arrive in the village of Ugair where Rehmat Khan’s brother nicknamed Akhrote (Walnut, but I never got around to asking why such an impressive person was thus named) was awaiting us. Thankfully there was only tea with biscuits, but the man kept on insisting that he be permitted to take down a lamb. Someone told him I had sworn zan talaq against more hospitality and that finally put the matter to rest. It was already well into the afternoon and if we tarried any longer we would miss the visit to the shrine of Pir Gahno.

This was another story related by Rehmat Khan as we were coming down the hill. Some years ago while visiting the tomb of ancestor Gahno; he got into an argument with his cousin who minds the shrine. The burden of the argument lay on the poor quality of food that had been served up to our Rehmat Khan. The argument dragged on with the cousin defending himself as vehemently as Rehmat Khan attacked him until our man pronounced zan talaq: never again was he to avail himself of the hospitality of the side of the family that kept the ancestor’s shrine. Time flew and soon Rehmat Khan was invited to a wedding in that family. He said he could not attend because that would necessarily mean partaking of his cousin’s hospitality and he would automatically stand divorced.

This was serious business. Family pressure mounted: as an uncle (and a maternal one at that) of the bride and one of the family’s decision makers Rehmat Khan had to attend the wedding. The ceremony needed his blessing. With the matter of zan talaq niggling at the back of his mind, he attended the party and, naturally, dined with his cousin – an act that automatically affected his divorce. Therefore, to keep matters in legal order a mullah had been imported from Taunsa to officiate over the second solemnising of Rehmat Khan and his wife’s nikah. The needful was done that same evening and by the mullah’s decree the new marriage between the old couple had to be consummated within ten days. With a glint in his blood-shot eyes Rehmat Khan said he had come through colours flying high.

There was one setback, however. Rehmat Khan’s wife was no dodo. As soon as the divorce became effective, she demanded her alimony. The man was flummoxed. Five thousand rupees was a good deal of money. But his wife would have it no other way. She had been divorced and she wanted her pound of flesh. Rehmat Khan paid up before he could be re-married.

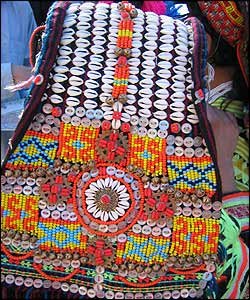

Pir Gahno’s shrine, like Granddad Musa’s, was again an unpretentious cement block cubicle with a single satin-draped burial inside. The obligatory peelu tree with its multitude of coloured cloth bags containing the first shaving of sons born by ancestor Gahno’s agency was right outside shading the cubicle. It suddenly shone on me: two Buzdar ancestors, Musa and Gahno, revered as miracle-working saints. If this wasn’t ancestor worship it was nothing in the world. Why, I wondered, hadn’t any anthropologist ever considered working on ancestor worship among the Baloch?

Baloch lore gives them Arab origin – as if that isn’t the case for all Muslims in the subcontinent. Serious research shows however that a very long time ago, much before the advent of Islam, they came from the shores of the Caspian Sea to spread out into the desert regions of eastern Persia and what is now western Pakistan. They descend therefore from an ancient Parthian bloodline. Long centuries ago and far away under the shadow of the Elburz Mountains Baloch religiosity perhaps centered on ancestor worship. The practice appears to have persisted even after conversion to Islam. Where others were encumbered with the invention of Syeds whose tombs could be worshiped for sons and wealth, the Baloch simply continued to venerate their own ancestors.

The last item on the itinerary was Khan Mohammed Buzdar. Three years ago while travelling through here with Raheal we had overnighted at the BMP post of Hingloon. They had shown me the slightly bent bars of the jailhouse and told me how one minute Khan Mohammed was locked up inside and the next was outside beside the free men. I had wanted to meet with the man and Raheal dispatched some of his staff to get him. But Khan Mohammed was away in Taunsa and I had to come away without the interview.

This time around, Raheal had sent word to Hingloon in advance that Khan Mohammed was to be made available. With ordinary build, gentle face and grey beard he looked like no Samson. He also spoke very softly. It was in 1962 or thereabouts, there had been a gunfight, said Khan Mohammed. He had shot and killed one of the rivals’ number which landed him in the lock up. Outside, his brother Taj Mohammed waited with some men of the other party. Shortly after the last prayer of the evening, he heard a gunshot and the shout that Taj Mohammed had been shot.

‘I was beside myself with emotion,’ said Khan Mohammed. ‘My brother had been shot and perhaps killed. I called upon Pir Gahno and before I knew it, the bars were bent wide enough for me to get out.’

The BMP men present in the courtyard restrained Khan Mohammed. Quickly he was hand-cuffed and shackled and returned to his cell. Meanwhile, it was also known that Taj Mohammed had only received a flesh wound and was out of danger. The bar-bending superman was once again human.

On our first visit one of the witnesses who had seen it all had told me he heard this almighty roar of ‘Ya, Pir Gahno!’ The next thing the man knew Khan Mohammed was standing beside him. Everyone was convinced it was Pir Gahno’s blessing that the man was able to bend half-inch thick iron bars. Khan Mohammed himself believed that as well. When I asked him if he could reenact the long ago feat, he said with great simplicity that he could not have done it then without the saint’s help and he couldn’t do it now.

All those who know of Khan Mohammed’s exploit, believe it was Pir Gahno who did it for him. He had called out the saint’s name and the saint came to his aid. I tried to tell them it was the saint, the superman that lived within Khan Mohammed and indeed within all of us as well. But that made no sense to them. It was useless to tell them how karate experts, having discovered through training the superman within, can use his powers at will. And how a shout focuses these powers to a single point to help them achieve the seemingly impossible feat of smashing a pile of kiln-fired bricks.

Khan Mohammed’s Pir Gahno had bent thick iron bars for him – but just one time. The Pir Gahno of karate experts does the impossible for them every time they wish. It is only for humans to discover the superman that lives within. My lecture made no sense. Neither to Khan Mohammed nor to the BMP men. Tolerantly they heard me out.

We left under a lowering sky. Sheets of lightning flashed on the southern horizon and I dreaded being caught up by a swollen stream. It was all right for Rehmat Khan who promised us more roast lamb if we could stay. Promising to return in case of a flood we finally bade him farewell. Thankfully it rained only lightly that evening.

Fellow of Royal Geographical Society, Salman Rashid is author of several books including jhelum: City of the Vitasta and The Apricot Road to Yarkand, Riders on the Wind, Between two Burrs on the Map, Prisoner on a Bus and Sea Monsters and the Sun God. His work - explorations, traveling and writings - appears in almost all leading publications.

Fellow of Royal Geographical Society, Salman Rashid is author of several books including jhelum: City of the Vitasta and The Apricot Road to Yarkand, Riders on the Wind, Between two Burrs on the Map, Prisoner on a Bus and Sea Monsters and the Sun God. His work - explorations, traveling and writings - appears in almost all leading publications.