Sunday, February 28, 2010

Steeped in history

This is Pakistan

A camel welcomes guests at the inaugural ceremony of National Solidarity sports festival in Rahim Yar Khan - Dawn.

Saturday, February 27, 2010

Puran Bhagat

Thursday, February 25, 2010

Appetizers

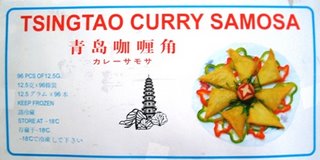

On our last trip to buy oriental grocery we were surprised beyond words to find 'Tsingtao Curry Samosa' and 'paratha - which taste like authentic Indian' in a refrigerator.

Both of these items were made in China. We immediately bought both items and I must confess they both tasted very good. Samosa filling was made of Chinese curry and parathas were puff parathas. You gotta taste them to belive me.

Today I couldn't resist and took these photos of 'made in China' samosa box to share with all of you. For those who are really interested in knowing the recipe' of this Chinese samosa, here are the ingredients which I am faithfully copying from the box: Cabbage, Wheat Flour, Water, Potato, Mushroom, Onion, Carrot, Vegetable Oil, Sugar, Salt, Soy Sauce and Curry powder.

I believe there is a big food export business going on between China and South Asia. On a trip to China in 2001, I met a businessman from Mumbai who was manufacturing 'Chinese dumplings' in India and exporting them to China.

Now after writing all this I must also advertise that China or India, no one can beat the taste of 'samosa' that are sold in United Bakery, Karimabad chowrangi Karachi. A sample is given in the photo above. A poet has also said in Punjabi:

jo maza chajjoo de chobaaray

O na Balkh na Bukhaaray

(The enjoyment that one gets socializing on a native street corner

cannot be found in intellectual cities like 'Balkh' or 'Bukhara')

Tags: Apetisers, Society, Owais Mughal

Monday, February 22, 2010

Faisalabad

In 1896, a new settlement was founded by Lieutenant Government Punjab, Sir James Lyall, in the area known as Sandal Bar. The plan of this habitat was prepared on the pattern of British flag by Sir Ganga Ram, a civil engineer, town planner and renowned philanthropist. The construction of eight bazaars and adjoining colonies was completed in 1902. There used to be sweet water well and an old `bargad’ tree in the centre where ghanta ghar was erected in 1918.

People of the city played an important role in Pakistan Movement. Quaid-i-Azam visited the `heart of Pakistan,’ as he called it, when annual session of Muslim league was held in the city. Over 100,000 Muslims of area welcomed the Quaid on November 17, 1942 and presented him rupees 500.00 in a reception held at Dhobi Ghat

Lyallpur, named after Sir James Lyall was initially called Pakki Mari. The name was changed to Fasilabad by General Zia ul Haq on the recommendation of a local photographer Aziz. Era of industrialization started in 1930 and Fasilabad was declared as an industrial zone in 1955. Earlier, complexion of Sandal Bar area changed with the excavation of Lower Canal originating from khanki in 1892. Presently, this `Manchester of Pakistan’ has one of the biggest and best Yarn Markets in the world. Fasilabad has grown the second biggest industrial city in the country after Karachi.

The world is becoming more urban as people are moving to cities in search of employment, educational opportunities and high standard of living. Population growth in Fasilabad has been very rapid. In 1947, the biggest of all the Kachi abadies in the country came up in the city that was later converted into Sir Syed Town and other residential colonies. Jinnah colony, Ghulam Muhammad Abad, People Colony, Afghanabad, Nazimabad and Ayub Colony came into existence in first 10-15 years after the independence. This human settlement of only 9191 people in 1901 (first census) is now home to three millions. The municipal area of the city has expanded up to 45 square Kilometres.

One of the main problems facing the city is congestion: in open spaces, public transport, housing, roads and streets. Presence of Goods Forwarding Agencies and oil tankers’ `addas’, Iron Market, Sabzi Mandi and numerous industrial units inside the city has adversely affected the cityscape. The administration has not been able to shift them out despite recommendations in Fasilabad Master Plan and complaints by the concerned citizens. Presence of these agencies in the city, particularly in the areas from Chowk Ghumti to old municipality office on Circular Road, Kachary Bazaar and Railway godown have made the lives of the citizens difficult. Though there is a ban on the entry of trucks and heavy vehicles between 7 AM to 8 PM under police act 23 but still much of heavy traffic can be seen in the city where a fleet of more than 52000 donkey carts is also playing. By the way, donkey carts have been banned to go downtown recently. An owner of a cart told that he earns between rupees 500 to 1300 daily. “The poor perform most of the manual labour in this rich city — which would be paralysed without its rehri walas. Their children work in life and health threatening situations: on power looms, kilns and in carpet centres. They live without any civic facilities,” he says.

Eight bazaars are the centres of trade and always bustling with activities. They are over crowded and full of encroachments. The shopkeepers and cloth merchants throw all the packing material — plastic and paper wrappers and other crap that cannot be sold — in front of their shops that are promptly lifted by children with large sacks on their shoulders roaming about in the markets for `raddi’ collection. A shopkeeper in Bhawana Bazaar told, “any thing that is not cleared by them stays there because sanitary workers of Fasilabad (FMC), responsible for keeping the city clean, do not perform their duties.” The city is divided in two sanitary zones each headed by separate health officer having an army of sanitary workers and inspectors on their roll. Thanks to FMC, even public parks are not being cleaned. “In an industrial city like ours, they (the planners) should look at every thing including waste as a resource and provide incentives for recycle business,” he says.

Punjab Government has banned the manufacturing and uses of polythene shopper bags but how seriously this ban has been taken can be seen in Fasilabad. One finds them every where. “The polythene bags along with other industrial effluents are causing soil pollution when they reach the fields being irrigated by Rakh Branch Canal” informed an official from Irrigation Department.

Green spaces and vegetation covers — so important for ecological balance — in the city are decreasing. The `green belts’ in front of the houses, particularly in Madina Town and People Colony have been turned into filth depots because people deposit their domestic waste out side their houses and no body comes to lift it or are being used for parking. Gulistan colony, Shamsabad, Ghulam Muhammad Abad and Fateh Abad are other neglected and adversely effected areas. One can see, smell, hear and even taste the pollution in the city.

Municipal bodies, city development agencies and the traffic police seem to be at war with each other instead of jointly serving the tax payers. Muazam Ali, a resident of People Colony complains, “what is our fault if FMC or traffic police fail to pay the electric bills? WAPDA disconnects the supply to the street lights and newly installed traffic signal system. We suffer in the process.” And, “WASA alone needs rupees 3392 millions to provide full fledged sewerage facilities for the people of Fasilabad by the end of year 2000,” informed an official of WASA during a briefing to a foreign delegation.

There is no single authority to coordinate and oversee the growth and development in the city that was laid out under the concept of radical planning with clear zoning of different land uses. People now have converted their houses into industrial units. The Fasilabad development authority (FDA) has been lying useless since 1982 for the want of funds'. The Director General has pointed out, in case it had escaped the public notice, that the FDA with many officers and no assignment should be downsized. On the other hand, FDA has decided to sell its 470 residential and commercial plots and other assets to over come its financial crises. Naturally, thefinancial crises’ are for the salaries of the FDA staff. What else!

The Agricultural University (established as college in 1906), Punjab Research Institute of Agriculture and Biology, National institute of Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering, National Institute of Fertilizer, Forest Research Institute, Textile Engineering College, Punjab Medical College, Government Degree college –where I participated in declamation contest in 1972 — and other educational institutions have played very important role in spreading awareness and education in the country. The government has promised to open an other university as well. But, sadly, “thousands of children in the city do not get the see the school, though. They are engaged in various forms of labour to earn for their living,” claims a socialite Muhammad Ijaz who is working to end this servitude in collaboration with ILO and other agencies.

The problems of Fasilabad are specific and need specific solutions. FMC with its small annual budget needs to improve the services, which profoundly affect the daily lives and well being of the people. Requirement: promoting democratic rule, exercising public authority and using public resources in all public institution at the levels in a manner that is conducive to good governance.

Marvi Love

Antiquity is the first message. The scenery is attractive in its own way. Goths (villages) and hills quaintly intersect the desert soil, open all around. The roads, wherever they are, swings and curves up and down. The vehicles bump up and down the roads and sandy track, giving fleeting glimpses of a rougher, more elemental existence. Villages pass by, with trees surrounding them and beautiful birds swashbuckling on the branches, like crows on a rainy day. The vegetation is reduced to the undergrowth and thorny shrubs. Cows move silently, hordes and hordes of them, jingling cowbells around their necks, and doves flutter in front of the moving vehicles, which may be struggling in the fourth gears. Fine waves of sand with bright silvery particles sparkle in the sunlight.

Sea was here in the past but it has now moved further south. That is why one still finds salt lakes along the roads. People of the area get the salt for their consumption from these lakes. Small mounds of salt are seen on the banks of the lakes. At places, crushers are seen working refining the salt and processing it into a powder form in the old fashion way.

British functionary Parker did so well in south-east Sindh that the district of Thar was renamed Thar Parker. But the things have not changed much since then in Thar region. The refusal can be felt everywhere. Whatever development has occurred in the other parts of the country, has bypassed Thar? The round mud dwellings with thatched conical roofs look good in photographs but may not be as comfortable to live in. Thar is supposed to be one of the most densely populated deserts in the world. If nothing else, one should remember how certain parts of the Thar had become the scene of battle during the previous wars with India. Once again it has become a political battleground these days.

Major attraction and one of the claims of the Sindh folklore to fame is the village Bhalwa where my curious sense was at its peak. Marvi -- Sindhi heroin famous for her chastity and patriotism -– lived in village. Just on the periphery of the village is a shed where it appeared that a tea stall had been set up during Marvi's melo (festival of Marvi). A few steps away is the "Marvi jo Khooh" (the well of Marvi) from where she used to provide water to her goats and sheep and where Umar Soomra had caught a glimpse of Marvi and had become so head-over-heels that he held the girl against her wishes. Lost in the magnificent stronghold, Marvi's longing for her native terrain gave birth to one of the most moving folklore of Sindh. Her tale has been immortalized by great Sindhi poet Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai. It is an integral part of our oral and folk heritage. Most Sindhi girls know all about Marvi. Ironically, Marvi is credited only with a dilapidated and poorly written sign in Sindhi and English languages.

Marvi has been treated in a manner as any other national legendary character. There is nothing inspiring about the village these days. The physical venue -- old well -- had been plastered over and totally replaced by an unmarked cemented structure, an absolutely uninspiring job. At the moment, the well is dry and no Marvi can come there and have her pitcher filled. All that is seen left of Marvi is her undying desire and ache for what is no longer there.

A mela organized here in her name has become one of the biggest social and business events in the Thar area. Local cultural committee organises the annual mela of one of the celebrated figures of Thar, with traditional zeal and enthusiasm. But the committee has no resources. Thousands of Tharis participate in the two-day mela. Scores of camels and horses are brought to the mela from various villages to take part in races. Malakhro (wrestling) also is held on the occasion. The stalls under shamyanas or in huts made of straw are set to do the business. One resident of Bhalwa said, "We Tharis realize that a nation which loses its connection with history soon loses its identity. Hence, we gather here to pay glowing tributes to Marvi, the legendary woman." Sadiq Faqir, Karim Faqir, Ustad Hussain Faqir, Yousuf Faqir, and Jeendo Khaskheli among other vocalists of Thar mesmerize the fans of the mela with their folk songs.

Further on the way from district headquarters Mithi to Nagar Parkar, Virawah is another important historic town. It used to be a seaport in the past. Remains and relics are scattered in and around this sleepy little town. But one notices the town afterwards. It begins just like any other typical dust and flies town on the roadside anywhere in remote Sindh, and it ends just as abruptly too. Before one could decide if this is the best place to explore, one is almost out of the village. The abrupt change in the landscape tells that village is left behind. Climb the nearby Karunjhar Hill and you can see landscape intersected by conical huts. At night I saw a series of lights from the hillock. Haloes of iridescent lights glowed in conical huts all around. This would be the place to come and take a look on Diwali nights when Hindu living in the area lit earthen lamps to mark the festival of lights I thought.

A segment of a wall existing there in the form of mountain of debris and some engraved stones give an ancient look in town that I photographed though the veracity of the wall's association with the past is yet to be discovered. But the site does give evidence of its distant past.

How do you people survive?" asked one of my more urban companions. "The greatest contribution of us Tharis is that against all odds we have kept the place inhabited for Pakistan," the answers came from one of the locals.

If those who are at the helm of affairs in the government have taken for granted that Thar does not occupy a significant place in the geography (and history) of the country, then they should read the Sur Marvi of the Risalo of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai. For the record sack!